PLACES

Places is a series that focuses on neglected rural areas in Africa. Places that often have a rich historical and cultural significance, but where basic government services are failing or completely lacking. These are places where I have walked through the burnt veld, waded through clear streams and have driven through and lived in. The names given to these places are markers of history, occupation, domination and environment.

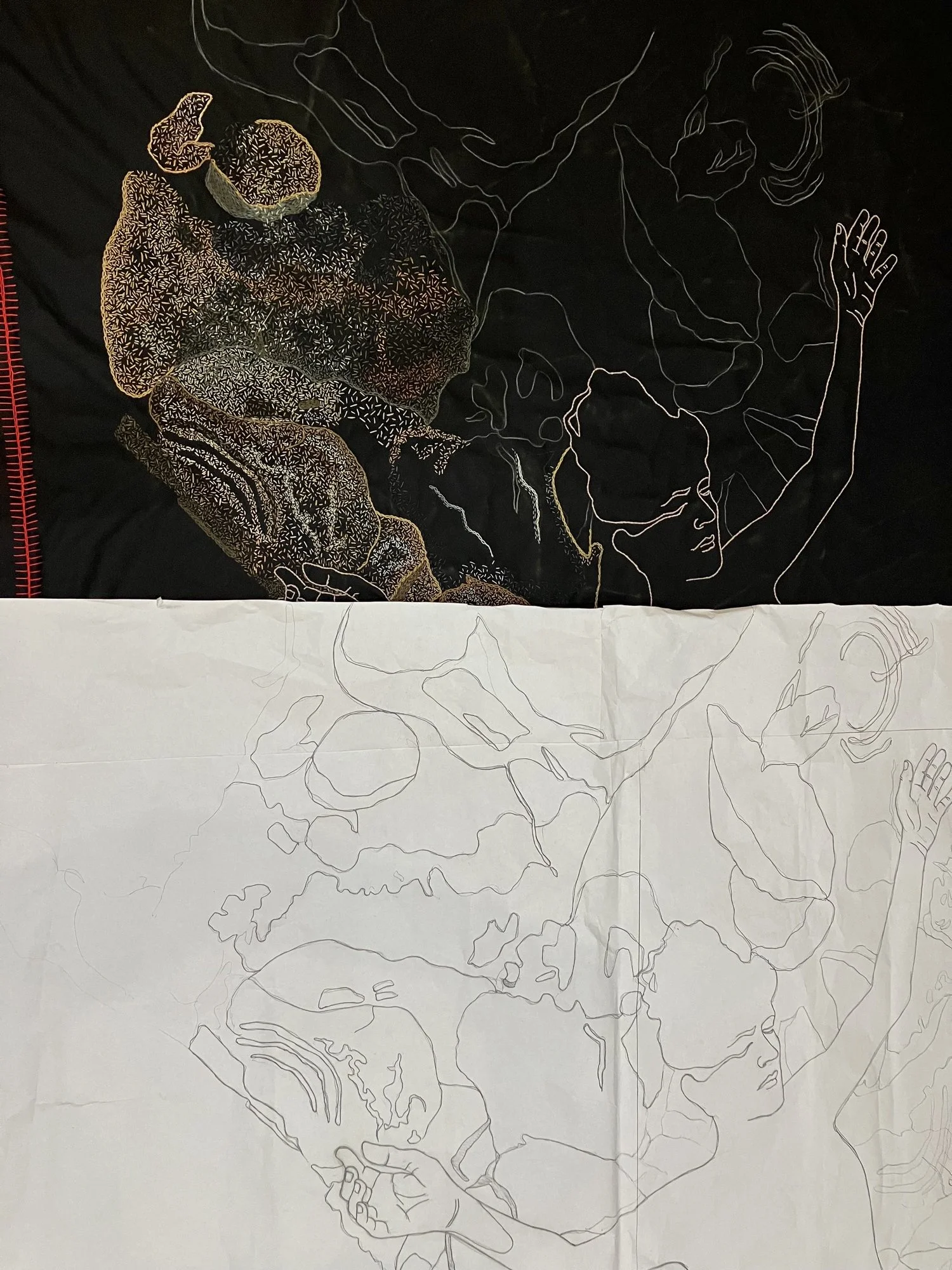

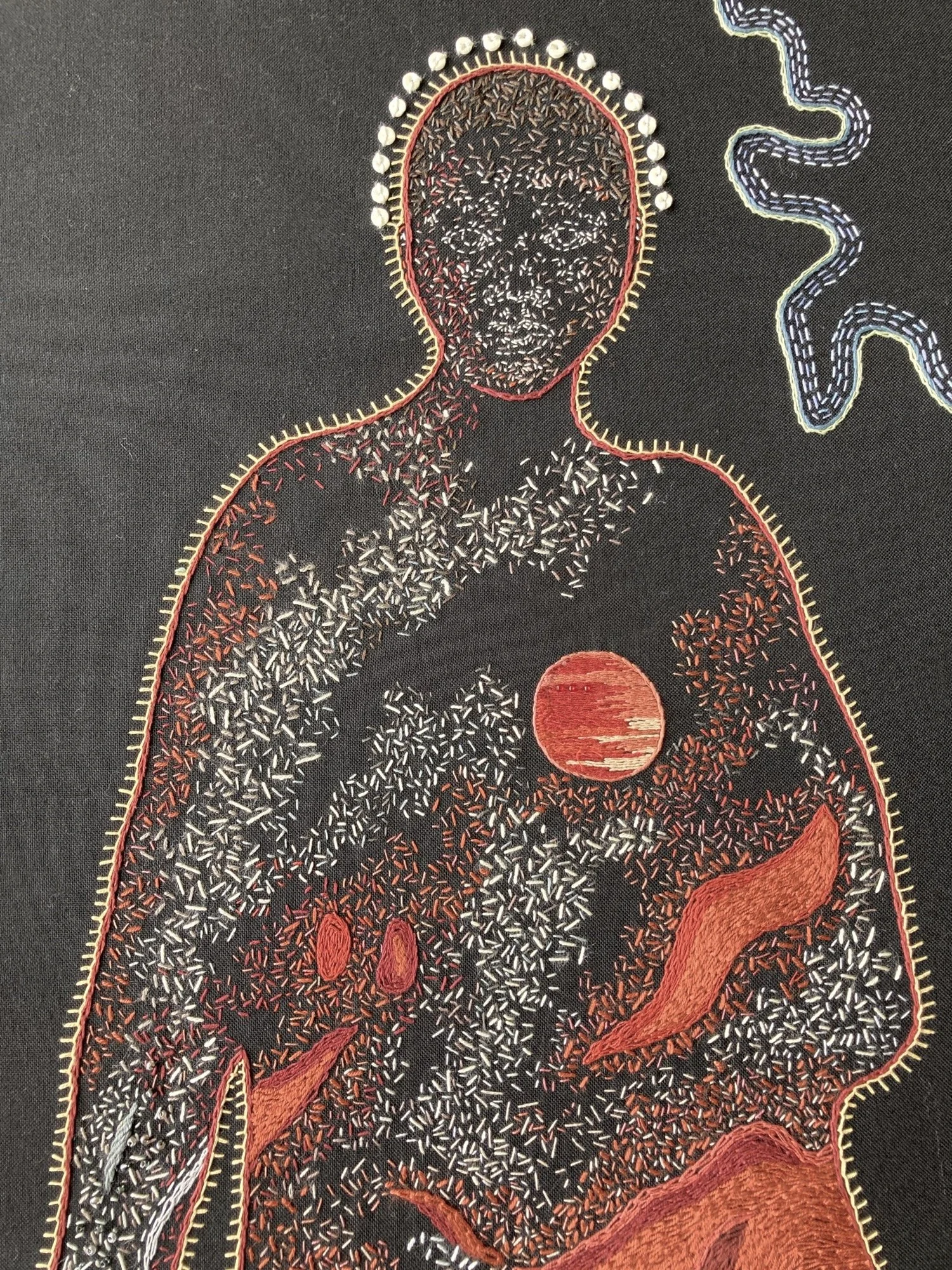

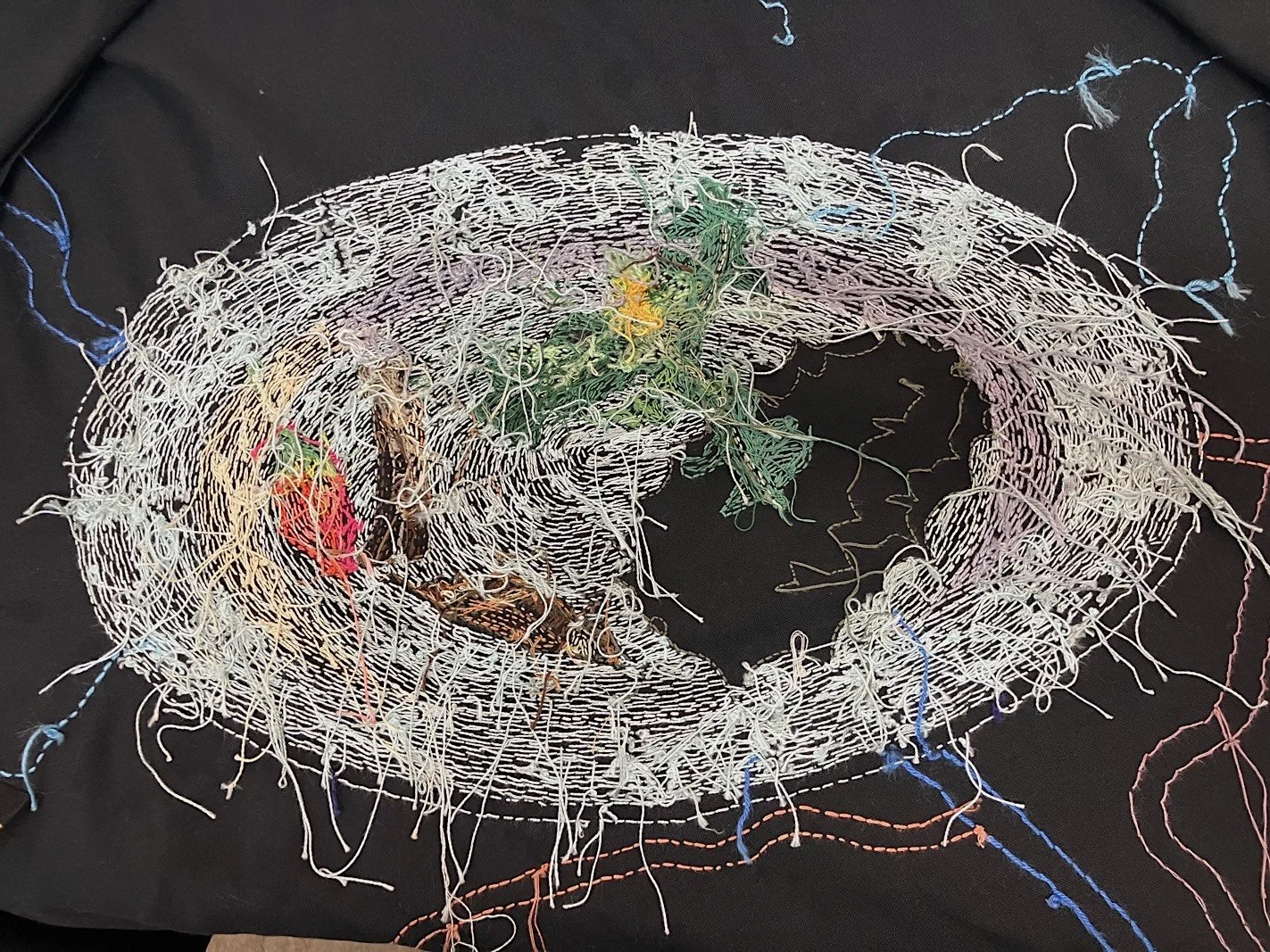

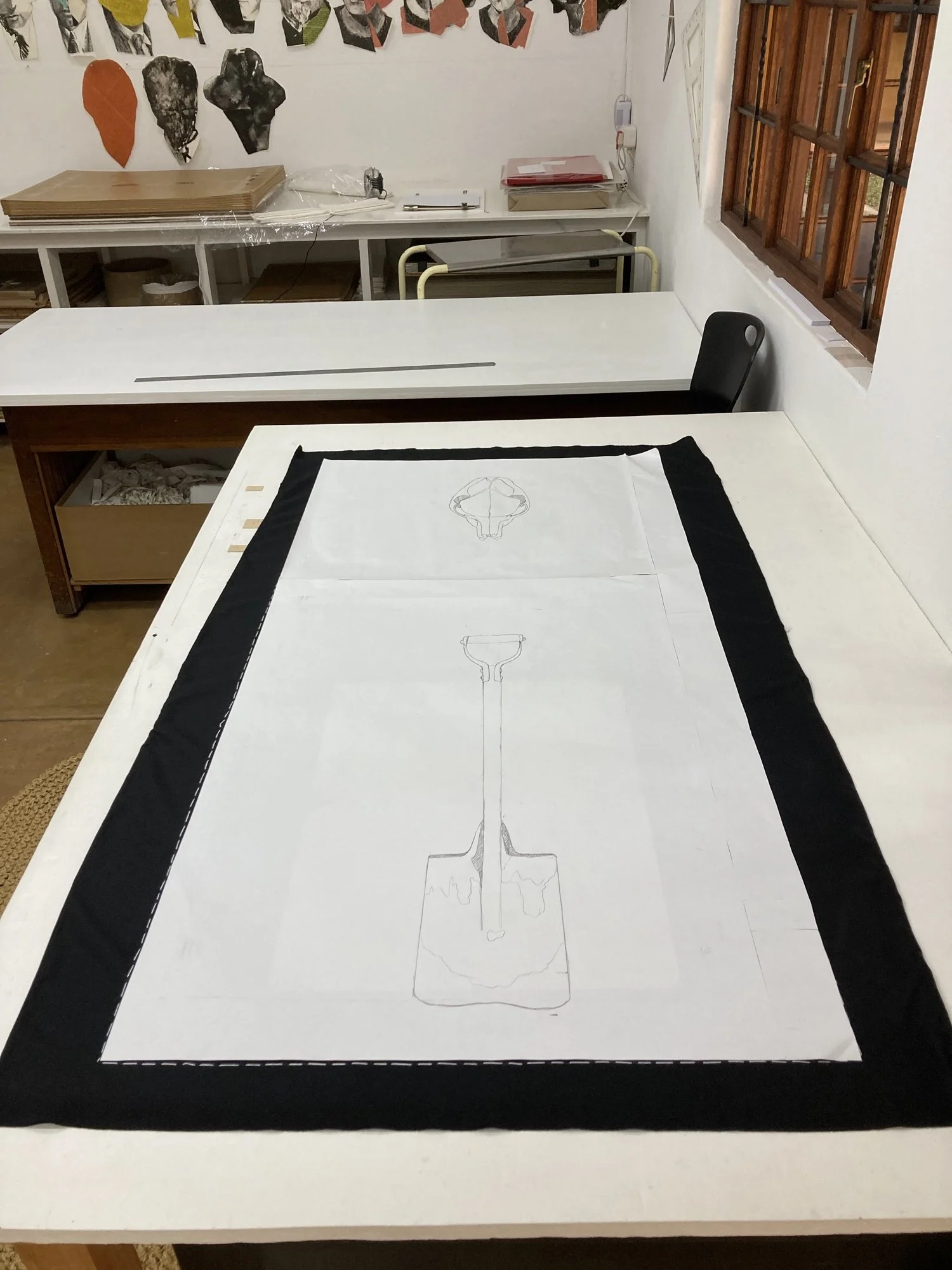

The artworks are arranged with a full image and detailed sections below it. Photographing work on black fabric is tricky; the close-up details provide a full sense of the work.

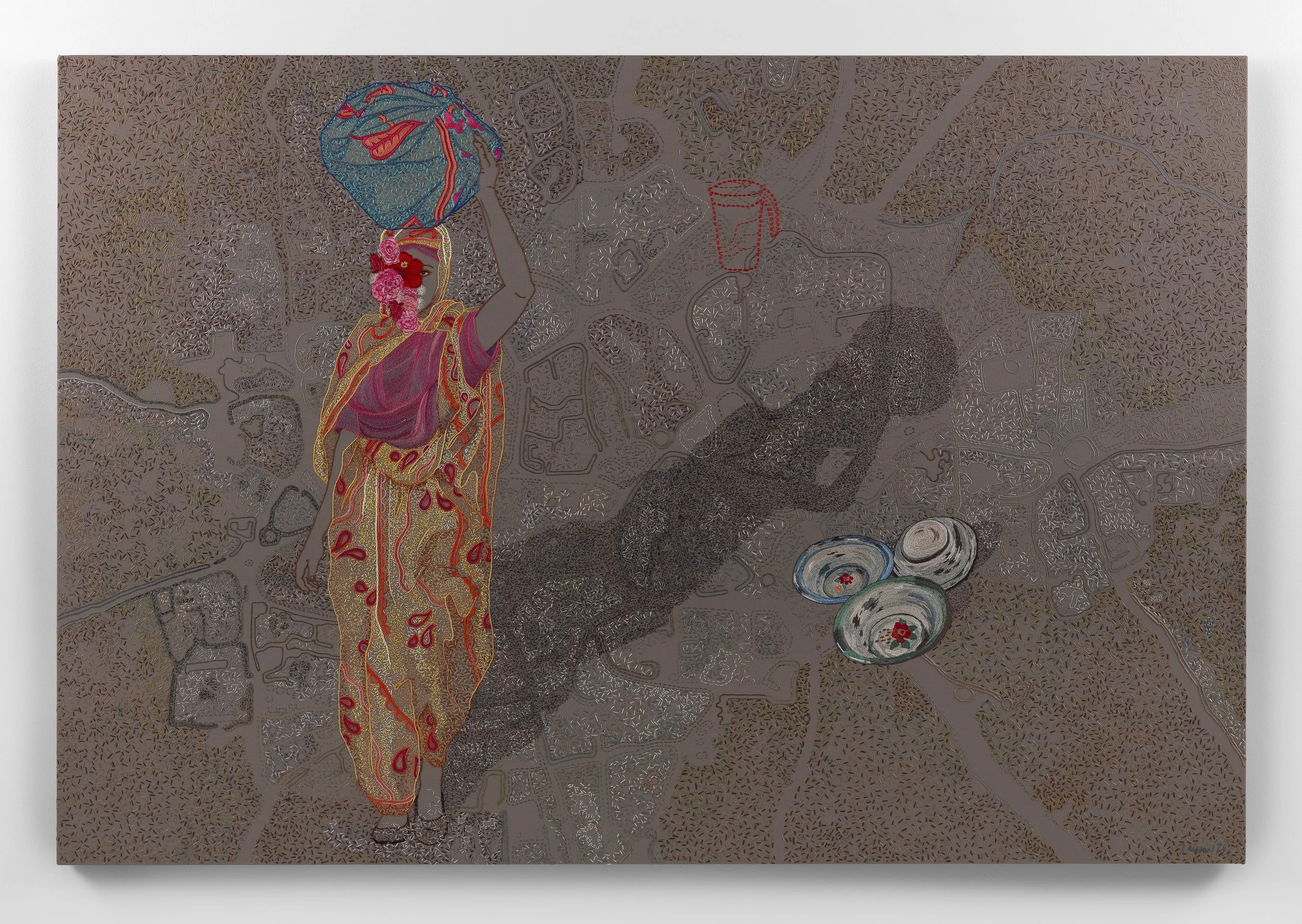

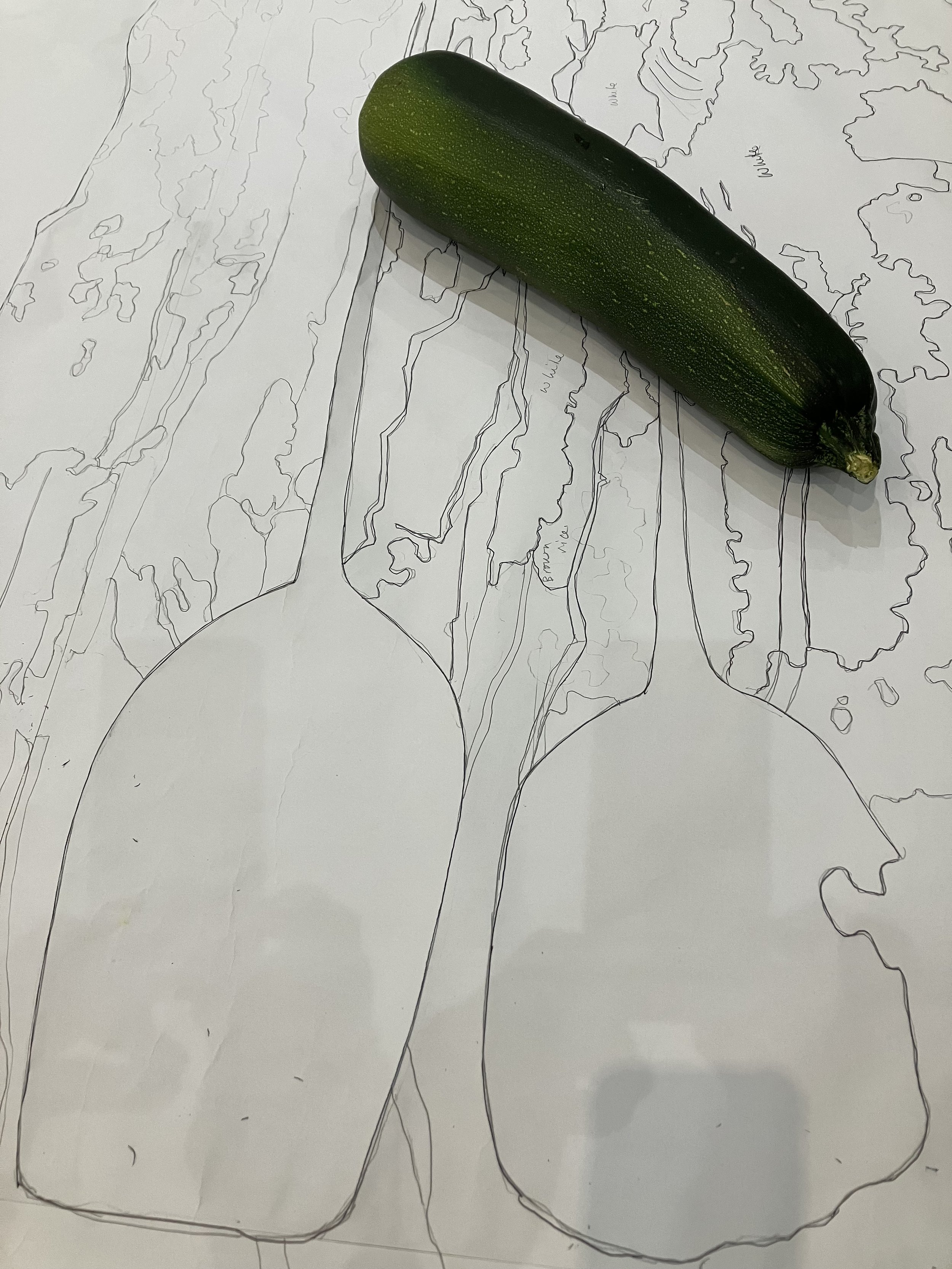

The piece is based on an ochre and specularite mine in the Makhonjwa Mountains, mined by hand for at least 20,000 years (based on an archaeological excavation at a similar mine in the same mountain range). This makes it one of the oldest mines in the world. It was still being actively mined until about the 1940s. Researching the mine, I came across photographs of women carrying ore from the site and in turn used an image of my daughter to pay homage to these women and the generations who walked across the same space. Women carried the ochre pigment away in baskets to decorate home exteriors, ceramics, their bodies and as a sunblock for skin. The mine is rich in iron ore, and this was used for millennia to make metal tools, such as the two hoes (the negative “drop” shapes in the right-hand corner) that were found near the site. The area also has a rich rock art tradition, and the artists would have used pigments from the mine for their images; the therianthrope with a female antelope head references this. Tree wisteria (Bolusanthus speciosus) thrives in the arid bushveld nearby and was flowering when I visited. In essence, the work is about women, art making and our earth-bound origins.

Pigment

Embroidery on fabric

187 x 118 cm

Available from Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London

El Geneina references the women and girls killed in El Geneina, Darfur. There are approximately 100,000 stitches in this piece. El Geneina is a city on the border with Chad that came under attack by the Rapid Support Forces and allied Arab militia in 2023. The Janjaweed destroyed Abu’s home, and he managed to flee to a refugee camp in Chad. Later, I was able to assist him financially to get his mother into Chad. I wanted each stitch to represent a woman or girl who has been killed, but trying to find accurate numbers for the people killed in the Darfur conflicts is frustratingly opaque. Genocide estimates vary from 200,000 to 400,000 people. These numbers make my 100,000 stitches seem insignificant. Hibiscus is the national flower of Sudan. I have also used flowers of the umbrella thorn acacia (Sudan’s national tree) and roses that grow well in desert gardens. El Geineina is Arabic for garden. Villages and homes have been bombed and burnt, leaving shadows of what was once there. Images that haunt me from Gaza to Sudan.

El Geneina

Embroidery on fabric

133 x 198 cm

Available from Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London

Brondal is the name of a valley adjacent to where I live. It is an Afrikaans word for source or spring valley, and is in turn derived from Dutch and German. More recently, it has become known as Magosha Valley by Siswati speakers. Magosha is a derogatory name for prostitutes. Part of the verdant sub-tropical Lowveld, the area has been exploited by industrial farming, first for planting eucalyptus plantations, and now for macadamia and avocado orchards. Along the road running through the valley, prostitutes ply their trade, using the cover of the trees as a place to service their clients. Prostitution is illegal and hence unprotected in South Africa. Like the women, the land is exploited whilst simultaneously providing.

Brondal

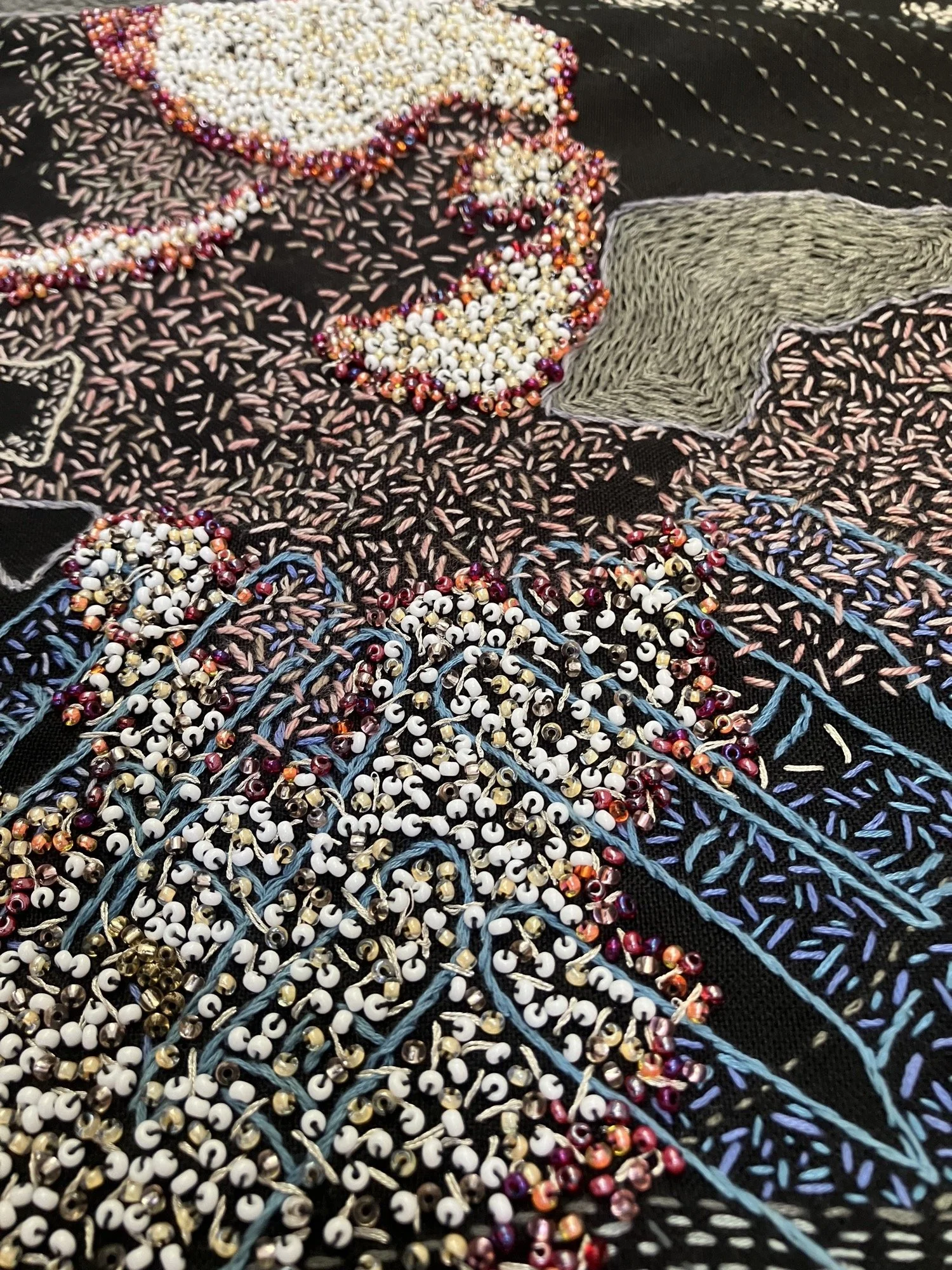

Embroidery and beadwork on fabric

198 x 118 cm

Museu Inimá de Paula collection, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Sefogwane is the Bakutswe name for the river, and Treur is the official name. Treur in Afrikaans means mourn or grieve. Floating in the pristine water of this river dissolves my sense of self. It is a personal place of healing, tears merging with water. Hendrik Potgieter, the trek Boer leader whose group gave the river its name (thinking that their leader had perished – he hadn’t), was a leading figure in the expansion of white settler colonialism. During the 1840s, Potgieter used the nearby settlement of Ohrigstad as his base for ivory hunting and slave capturing expeditions. The nearby Blyde River was named when Potgieter and his group returned safely from attempting to get Delagoa Bay; Blyde means joyful in Afrikaans. The two rivers run into each other. The dichotomy between what the river represents and the resulting tensions is still felt today.

Sefogwane/Treur

Embroidery and beadwork on fabric

160 x 234 cm

Private collection, USA

In the SePedi language, Mashishing is a place name derived from the word for good grazing grass; it has replaced the colonial name of Lydenberg. I am exploring the layered way that people alter the landscapes and landscapes in turn alter them. At Mashishing, there are hundreds of mostly geometric line engravings on the rock surfaces. Research indicates that these marks were made by the Koni people in the mid-1650s. The Koni were later assimilated into the Pedi. For generations, shadows have been cast on these stones as people have been removed from and have returned to Mashishing. Each time, the landscape leaves a mark on them just as they leave a mark on the landscape, the engraved lines linking the experience of now with then.

Mashishing

Embroidery and beadwork on fabric

198 x 118 cm

Robert Devereux Collection, UK

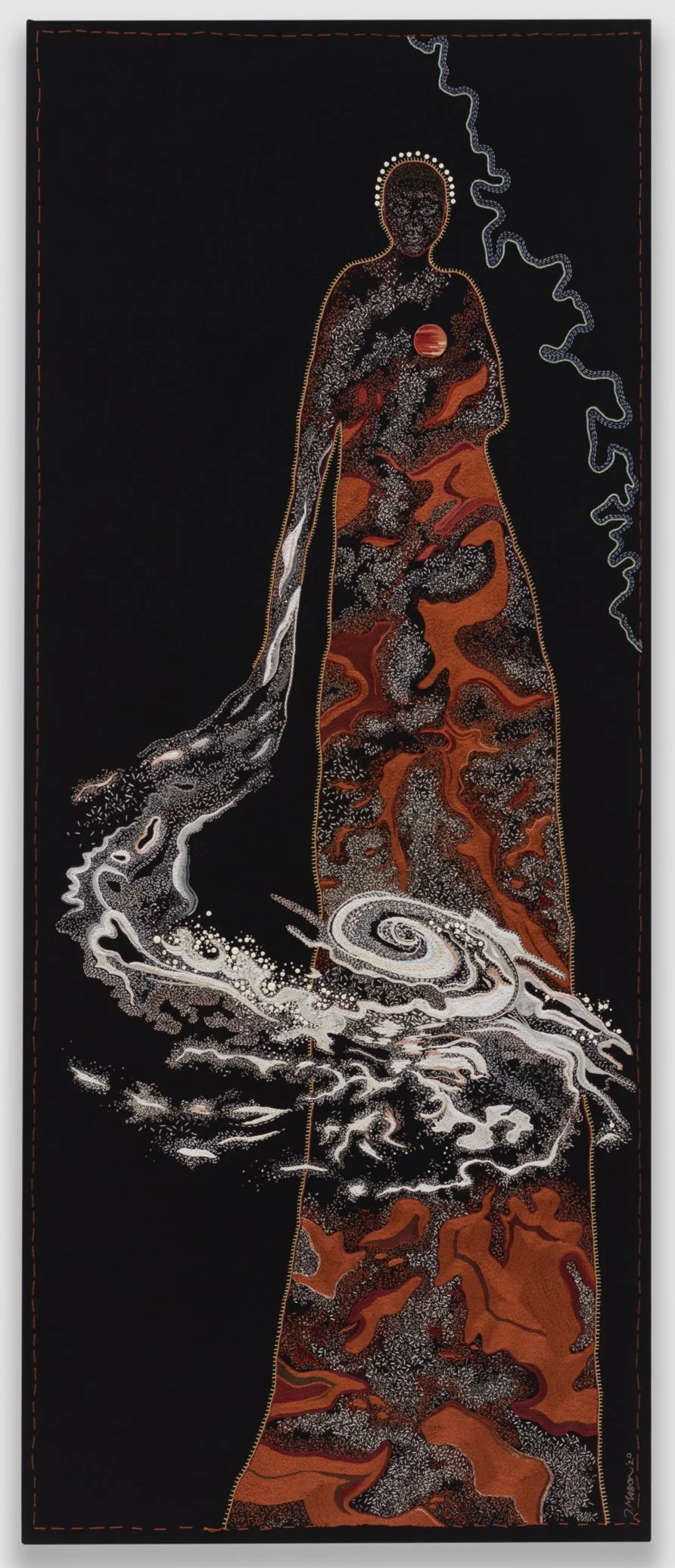

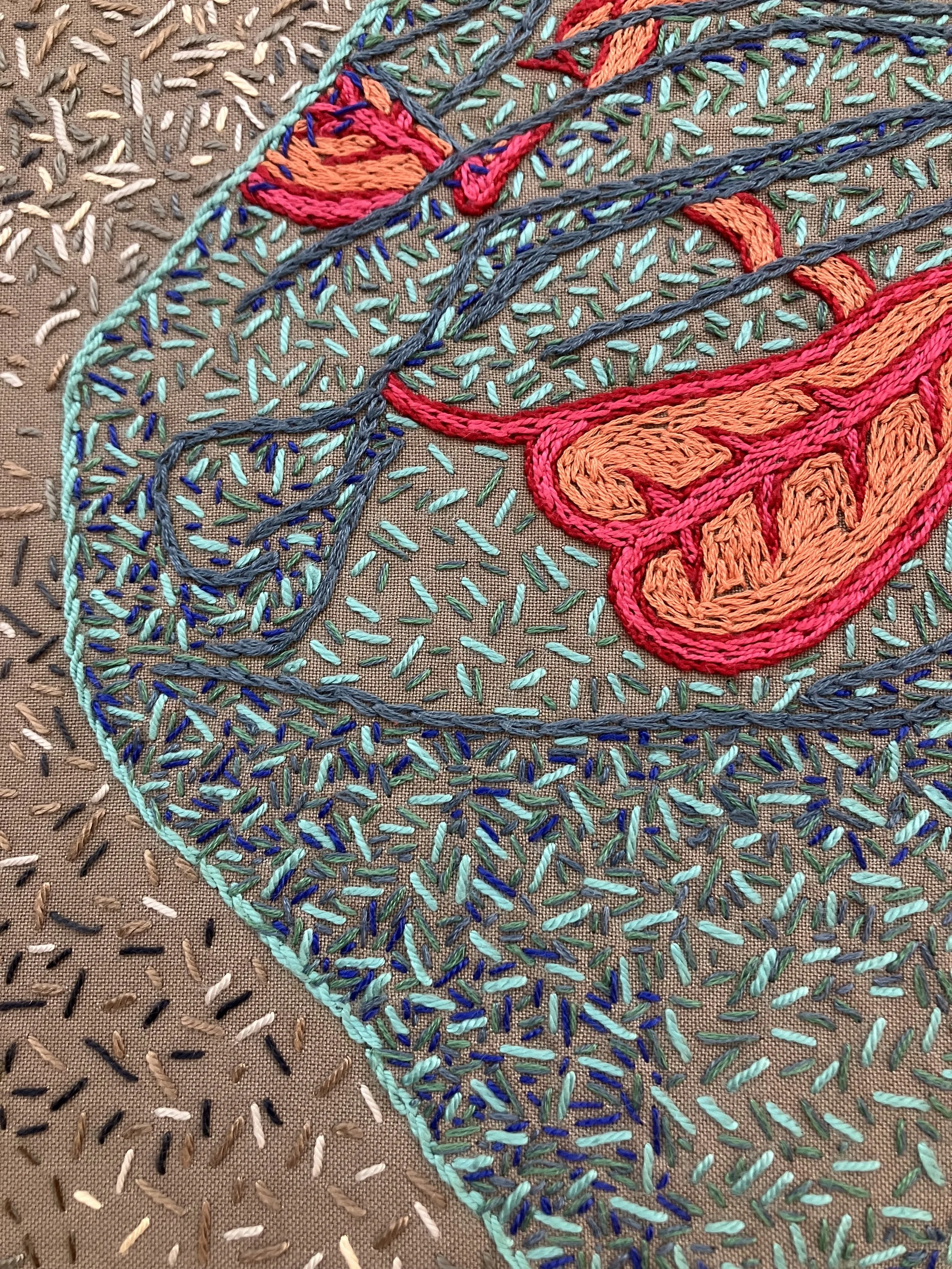

Driekopseiland is a site of mostly geometric rock engravings that are on a flat slab of glaciated rock, which forms a river bed in an arid part of the Karoo. Gmaap or (Gamaǃā) is the Khoikhoi name for the river. Based on archaeological evidence, it is thought that the engravings are between 2000 - 2500 years old. The concept of the water snake and its power to control rain is believed to be integral to the placement of the engravings. “Over and over again, we encounter the idea that the environment, far from being seen as a passive container for resources which are there in abundance for the taking, is saturated with personal powers of one kind or another. It is alive. And hunter-gatherers, if they are to survive and prosper, have to maintain relationships with these powers”. (Ingold, T. 1994)

The site is thought to be associated with female initiation, which would take place individually, and involve interaction with a water source and an offering to the water snake and the desire for soft, nurturing “female” rain as opposed to violent, potentially destructive “male” storms. Geometric tattoos done after a period of initiation seclusion would mark the end of puberty rites. The engravings would become animated by water flowing over them, the river's ebb and flow depending on rainfall and drought cycles. The connection between the engravings, tattoos, women and place is central to the panel. The lack of certainty about their origins allows them to live and transform into a contemporary reality, a reflection on internal and external mapping of the environment seen today from aeroplanes at night and on car and cell phone maps. These are all ways that we understand a place, our relationship to it, and reach back with a visual connection to people in the past. The shadow form reflects my meditation on women who are simultaneously present and absent. A shared topophilia between women now and then.

Driekopseiland (Gamaǃā) ǂGamaǃā

Embroidery and beads on fabric

246 x 144 cm

Private collection, Brazil

The Gxara River is where a young woman, Nongqawuse, experienced a revelation that led to the Xhosa Cattle-Killing of 1856-7. Her millenarian vision predicted that all Europeans would be driven back into the sea if the Xhosa killed all their cattle and stopped cultivation. Millenarian movements, often a feature of societies profoundly disrupted by colonialism, centre around a radical apocalyptic vision and a return to plenty and pre-colonial power. Nongqawuse’s vision led to an estimated 350,000 cattle being killed and a famine that caused the deaths of roughly 70,000 people. The stress on the environment by the extractive reaches of colonialism is at the root of this tragedy. In a world that is still dominated by patriarchy, I am interested in the massive effect that young women’s voices can have on the course of history and how this ripples into the present fabric of the climate crisis.

Gxara

Embroidery and beadwork on fabric

223 x 92 cm

Institute of Contemporary Art Miami collection, USA

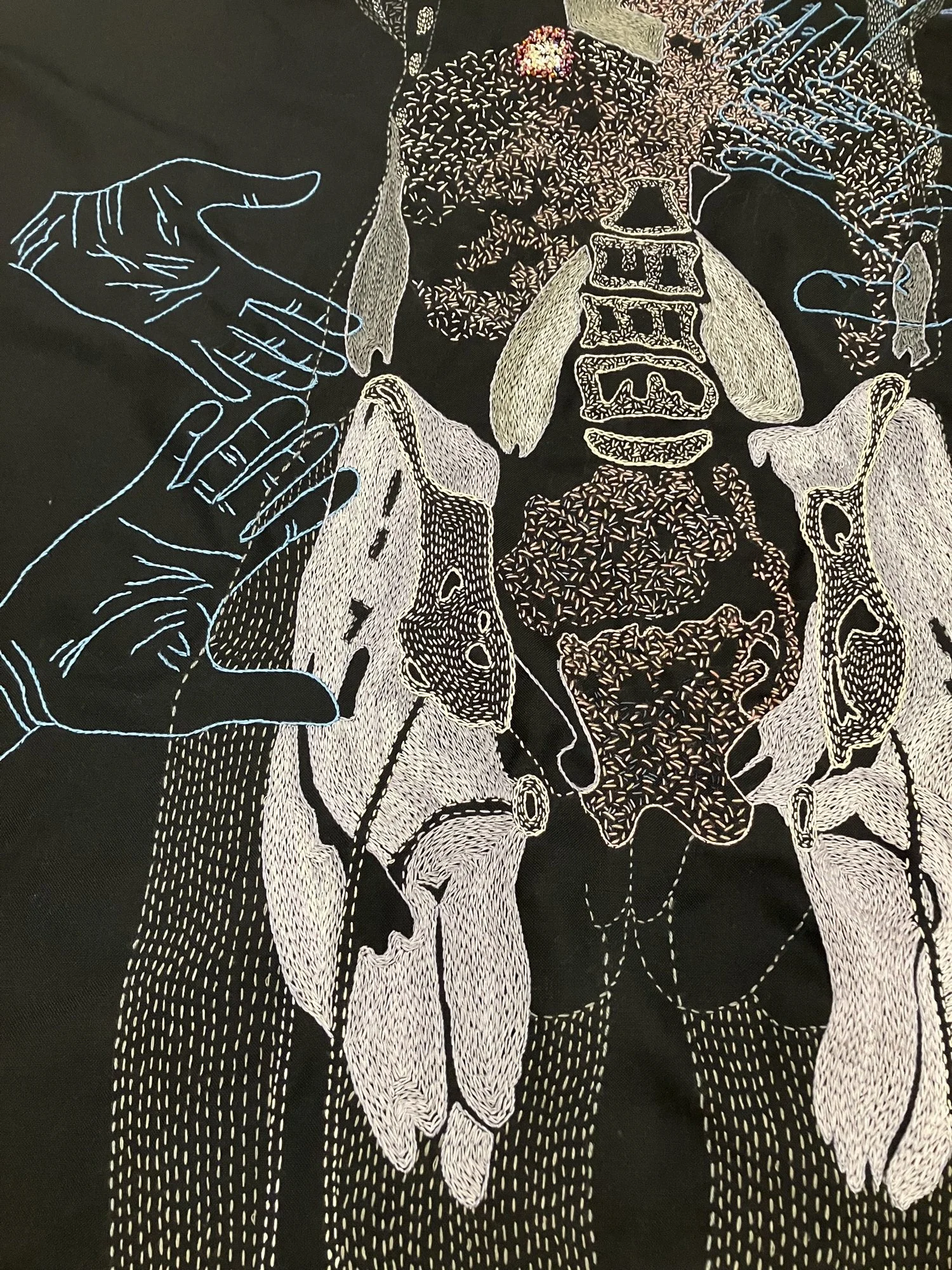

Locusts is based on news reports of women and children in the Eastern Cape starving and foraging for wild plants and insects to eat. There have been several cases where women have killed their children and then themselves out of desperation. Our urban-based politicians have become locusts. In addition, Locusts is a reflection of the wider climate crisis that makes it difficult for the poor to sustainably grow enough food to eat and support themselves. The map references are for central Tshwane and the Union Buildings (the official seat of government) and Peddie in the Eastern Cape.

Locusts

Embroidery on fabric

185 x 105 cm

Available through the Pippy Houldsworth Gallery (London)

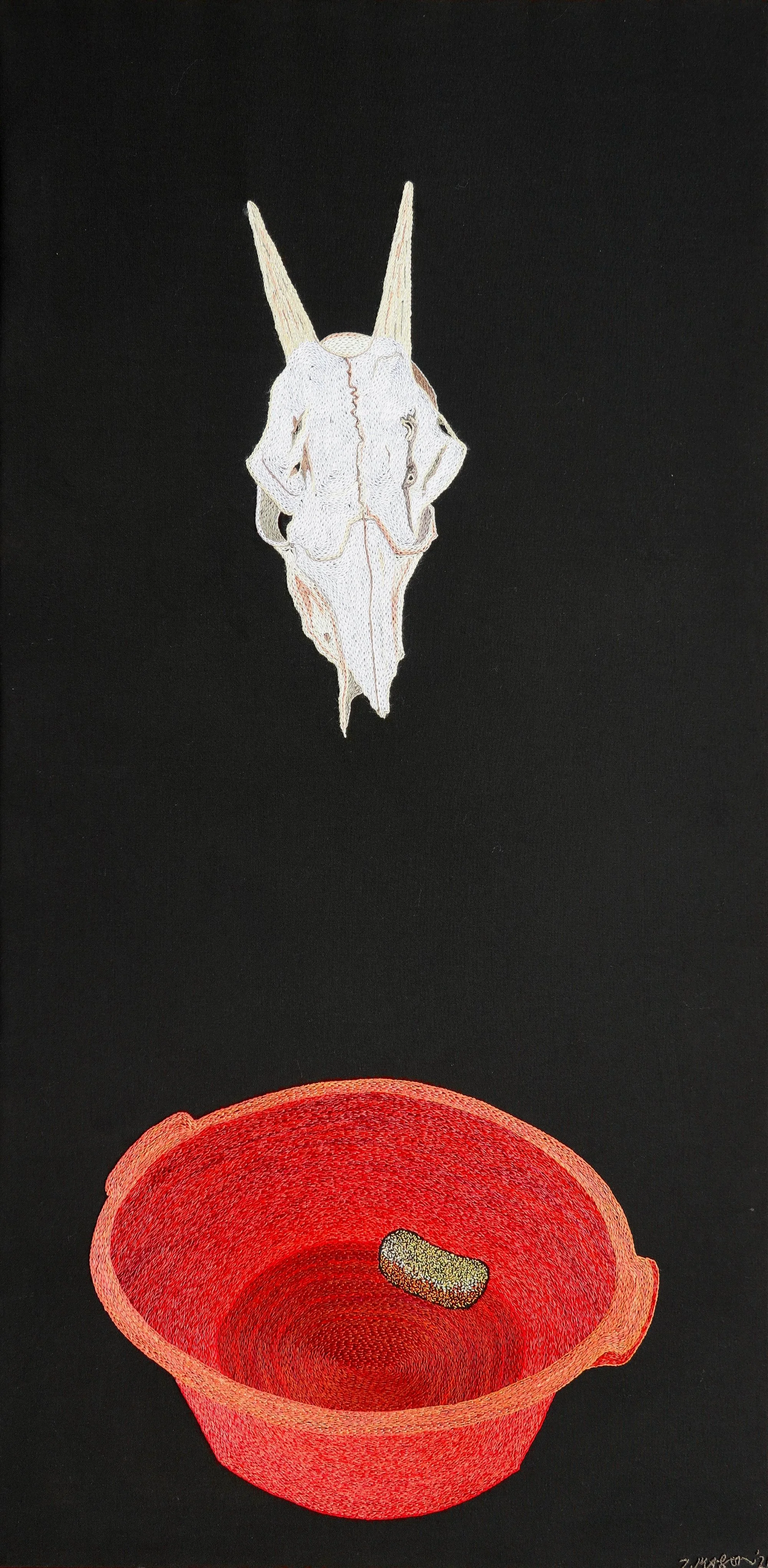

Mpunzi Kop is a community in rural Eswatini. The skull is a duiker (Siswati mpunzi), Kop means hill or head in Afrikaans. The washing bowl refers to a lack of infrastructure and delivery of basic services.

Mpunzi Kop

Embroidery on fabric

144 x 71 cm

Art Bank South Africa collection

Elandskraal is a small settlement in Limpopo. The name means eland enclosure, a fanciful idea that eland could be kept in a “kraal” like cattle. Eland are large antelopes and suggest bounty, in contrast to the arid scrub of Elandskraal.

Elandskraal

Embroidery on fabric

144 x 71 cm

Private collection Brazil

Jakkalsdans (Jackal's dance) was a refuelling stop on the Moloto highway, located in what was, during apartheid, a whites-only rural area on the way to an even more distant Black labour reserve. The Moloto highway is known as the ‘highway of death’ due to heavy use and neglect of controls. Driving past Jakkalsdans on my way to Kwaggafontein B, I would think of jackals partying under a full moon. Yellow plastic cooking oil containers are reused throughout Africa as water containers, and refer to a lack of safe state water provision.

Jakkalsdans

Embroidery on fabric

144 x 71 cm

Private collection Brazil

Emphisini is a rural area in Eswatini. It means the place of the hyenas. The mosquito coil refers to malaria, which, like a hyena, comes at night to stalk its victims.

Emphisini

Embroidery on fabric

144 x 71 cm

Private collection Brazil

Mochudi is one of the larger villages in Botswana. I lived there for three years in the early 1990s. This piece is a reflection on the place. A dassie (rock hyrax) skull and a spade. Walking up a rocky path in the village, I passed some young men carrying a spade. I asked them if they were off to do some gardening, and they replied no, they were hunting dassies.

Mochudi

Embroidery and beads on fabric

144 x 71 cm

Private collection, Brazil

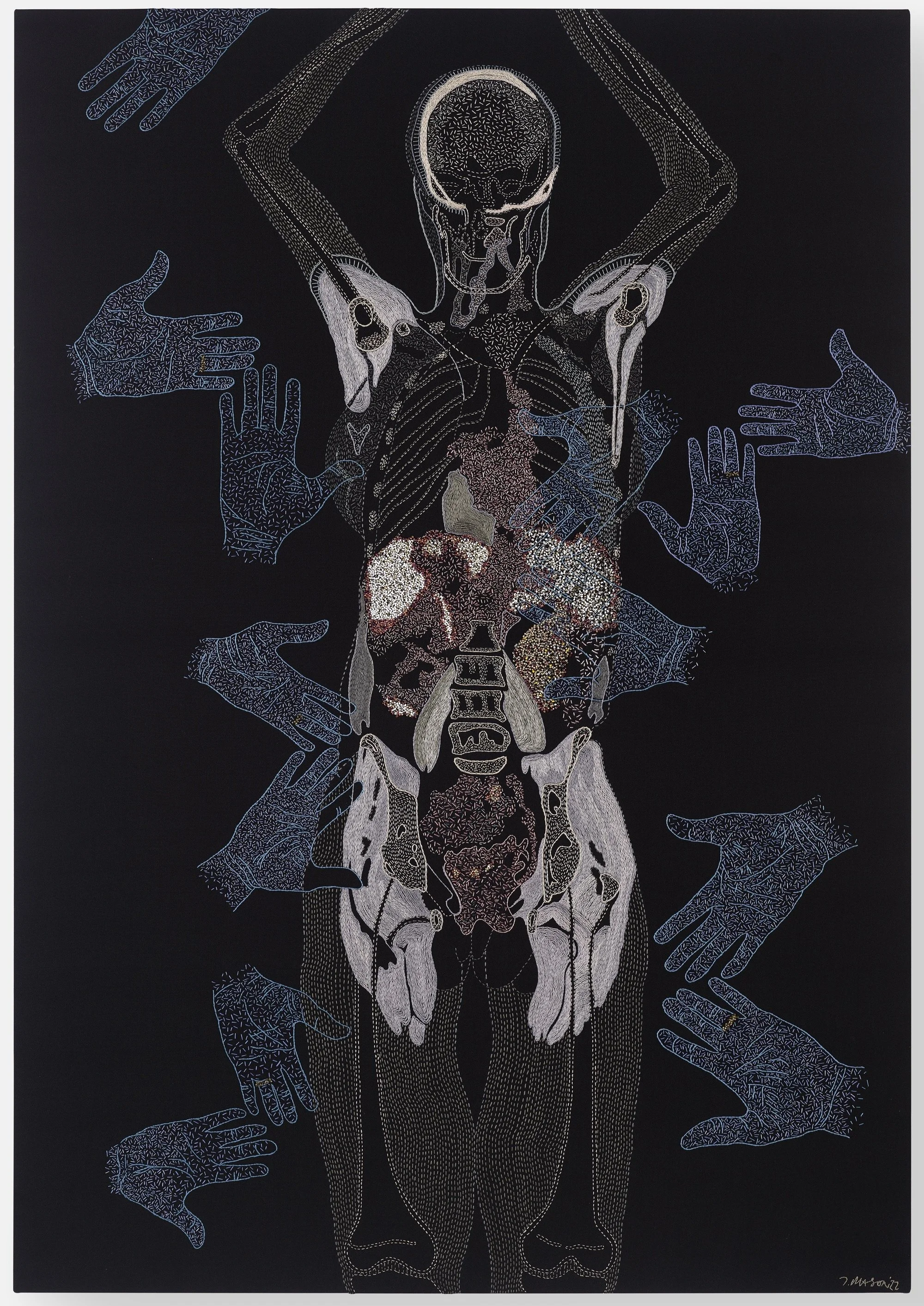

Gauteng is the Sotho-Tswana name for the place of gold. In Setswana, the name was used for Johannesburg and surrounding areas long before it was adopted in 1994 as the official name for the province. It is where I was born and where my paternal family moved in 1888 after the discovery of gold. Gauteng is the epicentre of trade, finance and medical facilities in South Africa. It is the smallest province in the country but the largest in population and economic activity. It is still the source of “gold” for millions of people. South Africa is rated as the most unequal country in the world. “In South Africa, the legacy of colonialism and apartheid, rooted in racial segregation, continues to reinforce inequality of outcomes” (Ed Stoddard, Daily Maverick 13 March 2022). It is into this that I stepped in 2020, taking advantage of my privilege to access globally leading surgical and nuclear imaging skills to save my life.

Gauteng

Embroidery and beadwork on fabric

169 x 118 cm

Museu Inimá de Paula collection, Belo Horizonte, Brazil